The Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing

March 4, 2021

Continued from previous post…

Even though it was only a few blocks from your father’s house, the next day you both drove his car to the coast. The Missing Persons song on the radio was accurate: Nobody walks in LA. Surely, the beach would provide a better experience than the previous evening. After all, this was sunny California! Girls would be everywhere. You’d have your pick. After trudging across a massive expanse of empty and hot sand, you dropped your towels a short distance from a group of teens playing volleyball. Their hair nearly white from the sun, they seemed like exotic creatures. You dared not approach. You lit up a joint, hoping maybe one of them would notice and invite you over. Didn’t happen. You decided to go for a swim, feeling foolish when you discovered how cold the ocean actually was. Nobody swam. Nobody walked. You didn’t understand California at all.

The whole trip was like that. You felt naïve and alone. Jesse’s up and down moods made it worse. You had hoped the West Coast was where you’d finally fit in, where everything would click. By the week’s end you couldn’t wait to go back to a frozen Chicago, the devil you knew.

You would return to LA many times, first to visit your father, and then for work, shooting commercials. Even then, with a great job and an expense account, a room at the Beverly Hills Hotel, you still felt inadequate and uncomfortable.

Refusing to accept such miserable feelings you chased the life you weren’t having. By then you were drinking and snorting cocaine. Many nights you sat in your opulent room, doing lines and watching pornographic movies on cable. Sometimes you’d go to the hotel bar and get loaded, fantasizing about the bombshells and starlets you would meet there. This too, never happened. Even the expensive hookers left you alone. What the hell were you doing so wrong?

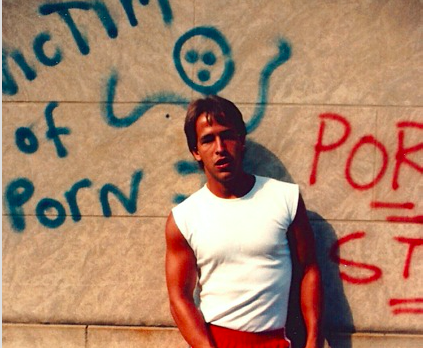

The teen-dream photograph beguiles you today because everything about it belied the truth then. In fact, you had trouble sleeping. You got drunk and high almost every night, and hung out with a crowd your father had correctly labeled as losers. You looked like a winner in that photograph. Yet, under the studly veneer was rotting milquetoast.

Ironically, as a child it had been the other way around: you were a smart inquisitive kid trapped in a soft, unappealing body. Getting both aspects right has been a lifelong struggle. Unable to reconcile the two you began dividing yourself. You were either the smart kid who enjoyed learning or the defiant teenager who got high all the time. The chasm grew wider with each passing month. By senior year in high school, you were two different people, with distinct and offsetting personalities: the double life of an alcoholic.

This was not to say you didn’t enjoy life or were depressed. You did and you weren’t. But you would constantly appease one personality at the expense of the other. Neither side ever developed completely or properly.

Though you eventually would lose the weight that insecure fat kid was always close by, rendering you sensitive and shy. The vulnerability was not lost on your peers, who found myriad ways to exclude you or take advantage. When you finally started getting noticed by girls, nothing ever clicked. You were as scared to be with them as turned on. They could tell, you just knew it. Oh, how you wanted them to think you were cool. But you had no idea what they wanted from you.

You could hold your own in school, got good grades, impressing your teachers. But to your peers it was a different story. Your long hair and concert tee shirts said one thing your report cards another. The smart kids could smell the cigarettes and marijuana on your denim jacket and deemed you a stoner, seldom inviting you to their parties. God forbid you showed interest in your education to the burnouts.

And so it went. Desperately trying to belong to one group or the other, never finding your place in either. You were like one of those hapless characters in Dr. Seuss’s story, The Sneetches. Were you a star belly or a plain belly? You had no idea.

You were not allowed to attend high school graduation because you’d been caught wearing shorts on the last day of school. You weren’t the only senior to have defied this rule but were unique in telling the Principal to fuck off when he busted you. Deeply upset, your mother viewed the ban as further proof of your increasingly reckless behavior. For your father it came as a relief of sorts; he wouldn’t have to drop anything more important in order to attend.

The Lizard King

February 24, 2021

Long, curly hair framing an impetuous, sensuous face; a chunky, beaded necklace clinging to his lean torso like the serpents he so often rhapsodized about, this was Jim Morrison in his prime. The photograph, taken by Joel Brodsky, captured the iconic rock star on one of the last days he would ever look this good, before degrading into a bloated, bushy alcoholic. A beautiful man who had it all, Morrison would be dead in four years. According to the photographer, Morrison was blind drunk during that photo shoot in 1967. You couldn’t tell from the pictures. He looked alive and virile. The camera had lied.

Not long ago, you discovered an old picture of yourself, shirtless playing table tennis in the backyard of your father’s first California house, in Santa Monica. Tanned and lean, with long brown hair, you were also wearing a beaded necklace. Was this your Jim Morrison moment, where you looked as good as you ever would? You remember not feeling that way. Like Morrison, you’d been a chubby kid. Those insecurities were still there even if the pounds weren’t. You recall being proud of your lean body but frightened by it as well. New skin or not, you trembled inside it. You looked cool but would never feel that way.

And just like your hero, you would become an alcoholic. You’d also written your share of bad poetry.

Goddess of burning urination

Clap Trap, A small-breasted nymph

Groveling for lust you succumbed

To pumping her indifferently

In this city of women

You lay dregs and drunken exceptions

Routine masturbations

Are cock and ball hand me downs

You’ve forgotten the rest, thankfully. It lies buried between sheaves of old papers somewhere in the garage. But the photograph brings it all back: summer break from college, visiting the old man in California. Looking at it now it’s tempting to think that this was the time of your life. Yet you remember that trip to LA as anything but.

The first night, borrowing your father’s car, you’d gone with your brother to Hamburger Hamlet, supposedly a cool place, according to your dad. You remember him telling you not to stay out late or bring home any chicks. He’d winked. You can still remember the envy in his eyes. Oh, to be young again, he said loudly as you paraded out the door.

But the evening was a dud. You were too young to order beer and you certainly didn’t pick up any women. You didn’t even speak with one. Entombed in a leather booth, you and Jesse tried valiantly to look like you had it going on. In a half hour you were done eating. It was painful. The sun hadn’t even set. You couldn’t go home now. Your dad would be so disappointed. The two of you decided to drive into Hollywood and check out the strip. You smoked a joint and turned up the music. But no amount of posturing could hide the fact that you were a couple of clueless teenagers in their dad’s Honda. You’d spent the rest of the evening killing time, waiting for it to be late enough to return home with a semblance of your dad’s fantasy intact.

to be continued

Why Are You Here?

December 11, 2020

He was “a piece of shit junkie.” His words. Clean almost a year Jake begins a harrowing lead. His entire family are addicts (active or dead) and, not surprisingly, he had started using early in life, in the 5th grade, whatever he could get his hands on: weed, booze, cocaine, meth… Then he tried heroin. And like so many others before him, junk quickly became the apex predator of his body and soul. The warm embrace was a python. It did not let go. He tried to free himself from its grip; spent nine months in rehab, only to get loaded within days of his release. “It was the same as ever,” he said, “only worse.” Jake’s mother, a methadone addict, gave him a piece of advice based on her experience: “Just stop trying, son. It ain’t worth it.”

Remarkably, he did not listen to her. Instead, he took the “rock star cure” and spent a brutal week detoxing at the Four Points Sheraton. Luckily, Jake had some friends left in the world. From the hotel, they drove him to a rehab and this time it stuck – so far anyway, one day at a time. Jake credits the facility’s emphasis on AA for getting him this far.

As is custom, he must now choose a topic for the group’s discussion. “Why are you here?” He asks.

Great fucking question, capturing the long-term implications of sobriety as well as its immediacy. This meeting. This evening. When you share you typically respond to the speaker’s lead rather than the suggested topic. This time you answer the question:

“It was 7:40 pm, the sun was setting, my family was out doing their thing, the dogs were asleep on the floor. I was alone. I had a few hundred dollars, a car, my laptop, and my phone. I had everything I needed to get into all kinds of trouble. I didn’t want to drink or get high but I wanted something. Desperately. I just couldn’t put my finger on what it was… I never can.”

The Big Book calls it being “restless, irritable and discontent.” Yearning caused by the hole in your soul; something you used to fill with vodka and pills. Sober a long time now, there is still a cavity with a drain at the bottom and its pull is intense. You reckon with yearning every day and especially at night. AA suggests you ask God to remove its power, its gravitational pull, to fill yourself up with Him. God released you from the bondage of drugs and alcohol. Therefore, he can release you from the bondage of self.

“Alas, I’m not the praying kind,” you tell the group. “When the yearning washes over me I need to do something tangible. I need a safe place to go, a lifeboat. I need this group. That is why I am here.”

Letter to my Professor at Berkeley. Just because…

November 22, 2020

My philosophy as it relates to diagnosis and treatment has evolved since I first became clean and sober in 2003. While I began (and continue) my path to recovery as a member of Alcoholics Anonymous, I have never completely accepted a number of its foundational tenants. For example, I remain uncomfortable ascribing to the disease model espoused by AA (and elsewhere). I believe every person with a substance use disorder played a major role in creating their problem (routinizing bad decisions), and they will need to do the same in recovery (changing the behavior). I recognize the usefulness in calling alcoholism a disease in terms of framing the therapeutic aspects of 12-step recovery models and in determining healthcare policies, qualifying for insurance, etc. Like with any disease, I also believe that alcoholism and drug addiction are progressive in nature.

As a counselor, I adhere to the five ethical principles: Autonomy, Beneficence, Fidelity, Justice and Nonmaleficence. Realizing that while each has specificities all are beholden to the other. Indeed, one may be in conflict with another, such as confidentiality and the potential for imminent harm. Untangling a sticky ball requires a measured hand. In a given situation, if right and wrong are not crystal clear, my intent will be to discuss options and scenarios with my peers before acting. One of the most important words booming from your lesson plan: CONSULT! I look forward to that collaboration.

The first thing I learned in Journalism school there is always two sides to a story. Likewise there are multiple stories for every individual who suffers from alcohol or chemical dependency. A person’s drug narrative is often shaped by their genealogy as well as environment. Things like family structure (or lack thereof), social groups, ethnic and cultural norms and other issues almost always play a role in the formation of a substance use disorder. How could they not? Therefore, a counselor worth his or her salt must be culturally competent beyond what passes for acceptable in today’s divisive political climate. Working in the field I know this is an area I must continue to develop, letting go preconceived notions I may be harboring.

Specifically, regarding your class, I very much appreciated the flow, tone and manner of each session. Given the myriad technology issues and the upside-down nature of 2020, I found this course almost therapeutic! Yes, it was a lot of work but the curriculum was such that I could immerse myself in it, whether absorbing content or creating it. So… thank you!

Like many of my classmates reported I also enjoyed and appreciated the role-playing activity. “Practice” like that is always appreciated. Yet, my favorite part of the course was/is the active discussion concurrent to your lectures. Spirited discussion with peers and professor works for me; I like learning this way!

Creating my presentation piece was, dare I say, fun. Immersing myself into the content was of course beneficial from a learning perspective. But the assignment was stimulating from a creative perspective as well. Making slides. Creating graphics. Presenting to the team. Giving and receiving these presentations was time well spent.

Finally, thank you Dr. ——- for your efforts in trying to keep the Certification Program going. Whatever happens, I appreciate knowing my commitment to this coursework is valued beyond its profit margins or lack thereof.

The Acorn

November 16, 2020

On the last day of your senior year in high school you broke a rule by wearing shorts. The Principal called you out for the infraction, stopping you in the hallway. The details of your exchange are lost in time but you most certainly had been disrespectful. Whatever the case, he ended up banning you from the graduation ceremony. A harsh blow, but hardly the first one the school had dealt you during your tenure. Thankfully, it would be the last. Good riddance. Your mother was upset by the news. Maybe she cried. Maybe she took your side. You don’t remember. It was a long time ago. However, you do recall your father’s reaction. “Good,” he had said. “Now I don’t have to go.” You were relieved that he hadn’t gotten mad. But was it also possible that you’d been hurt by his indifference to your banishment (and by proxy his). After all, had you not been banned from the ceremony your father would have been forced to attend. At the time you viewed it as a win: neither of you sitting in the hot sun waiting for a piece of paper. But shouldn’t a father want to go to his son’s graduation?

The acorn does not fall far from the tree. Having three children, you too are put off by the myriad events you were made to attend. Parent-teacher conferences. Recitals. Soccer matches. Graduations. You were ambivalent about going to any and all of them. Sarah hated this about you. “Why must you only think of yourself?” She asked a million times. As time wore on, she would become even more direct: “You’re going, whether you like it or not.”

And go you did. Sometimes grumbling, rarely happy about it, always happy when it was over. You have wondered about this attitude. Many times. It’s not that you didn’t want your children doing these things you just didn’t want to do it with them. It was nerve wracking watching Remy hammering away at the piano or Callie being bested on the soccer field. Worse was enduring the other children. That was the opposite of entertaining. What did Oscar Wilde once say? Hell is other people’s children. They bored you to annoyance.

But you went. Dutifully. You have Sarah to thank for this.

After joining AA, you learned to name your character defects and that your principal sin was one of self-centeredness. Early on, you recall a member’s lamentation about drinking in his car while his daughter played the cello. How low can one go? He asked the group. Join the club you wanted to say. It went without saying.

Your upbringing demanded that you become self-sufficient. Your difficult surroundings forced you ever deeper into your head, where you created fantasies to offset the growing fears and frustrations of the outside world. You became introverted and built your life around it – it being you. Reading, writing, collecting butterflies, drawing comics, even masturbating; by the time you started using drugs and drinking the die had been cast. You put yourself first because in your mind no one else ever would. You had ample evidence to support this view. Your parents abandoned you. Friends betrayed you. Girls were beyond you.

You have covered this territory before: in therapy, in AA, in your writing, in your head, ad nausea. Even during your darkest hours, you knew better. That’s why you intervened on yourself, joined AA. What you hadn’t counted on was “better” meaning selfless. You desired to be a better husband and father but you couldn’t let go of your will. Despite everything, you admired your wits and what they had wrought. In AA, you heard people attack such pretenses over and over but… There was always but. Needless to say, untangling yourself from your self has proven to be tricky. A lot more tricky.

Even so, there is much to celebrate. You are not so angry anymore. You are responsible, law-abiding, and paid your taxes. You do not feel cheated by the world or anyone in it. Though you know the world is unfair you also realize that this is why you are still alive and not a drunken statistic. If life were fair you’d be dead. You are grateful for what you have. You are sober.

Every day you do something physical, something spiritual and something for your brain. You have your set of unwise and unhealthy behaviors but it soothes you. It could be worse.

But the calm always seems conspicuous. Can you maintain it? Will another front arrive? The questions buzz like mosquitos, disturbing the peace. What now?

The Happy Soul Industry

The Happy Soul Industry The Last Generation

The Last Generation